Having more than one collecting interest can produce some fascinating intersecting lines.

by Jay Hoster

James Thurber—full name James Grover Thurber—was named for the Rev. James Grover, a Methodist minister who was a friend of his grandfather William

Fisher and the first city librarian in Columbus Metropolitan Library. The parlor in the Fisher house had a large portrait of the minister on the wall.

In The Thurber Album, Thurber comments, “I often thank our Heavenly Father that it was the Reverend James Grover, and not another friend of the family, the Reverend Noah Good, to whom the Fishers were so deeply devoted.”

While that sounds like an example of Thurber’s whimsy, it turns out that The Reverend Noah Good was indeed a real person. He has a place in the history of Riverside Methodist Hospitals (J. Virgil Early, Creating a Vision, 1991) as the superintendent of a predecessor institution.

In My Life and Hard Times, Thurber tells the story of a production of King Lear at the Colonial Theatre in which Edgar’s “Tom’s a-cold” speech (Act 3, Scene 3) is interrupted by the Get-Ready Man calling upon people to get ready for the end of the world. Thurber writes, “They found him, finally, and ejected him, still shouting. The Theatre, in our time, has known few such moments.”

The Get-Ready Man was not a Thurberesque creation. In her compilation of Columbus people and places entitled You and Your Friends (1906), Mary Robson McGill had an article with the headline “Get Ready for the End of the World.” McGill asked her readers, “Did that cry startle you? Columbus people are accustomed to it. For many years, that gentleman, Mr. Willard P. Walters, has been calling, ‘Get ready for the end of the world,’ but some way Columbus and the old world move along without making any special preparation for the interesting event he predicts.”

One item in my intriguing Thurber collection is a postcard of an early Ohio State game in which the final score was Ohio State 18, Case 0. According to my go-to resource for OSU football history, Marv Homan and Paul Hornung’s Ohio State: 100 Years of Football, the score places that game in the 1913 season. That was Thurber’s freshman year at Ohio State, and while it might be tempting to think that he would have been one of the people in the stands, he was more likely to have been in the library reading Henry James.

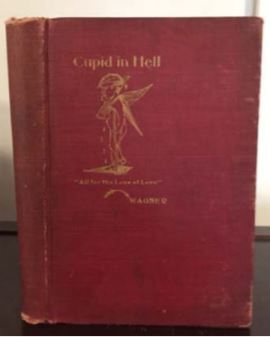

Among my Columbus collectibles with a Thurber connection is a well-read copy of a book written by Clara Eleanor Wagner, Cupid in Hell, published in December, 1910. The illustration on the front cover shows Cupid with his arm in a sling and shedding tears. The frontispiece portrait shows an elegantly dressed woman with a furious expression who looks a bit like Katherine Hepburn. The book’s protagonist is named Frances Eleanor Vendahl, clearly intended to be the author’s alter ego. Vendahl is married to a man named Harrison, and in her description Wagner rhapsodizes about “how handsome he is.” The book is filled with verbiage worthy of a Harlequin Romance: “My sweetheart lifts me up and holds me out at arm’s length—how strong he is!—and says, ‘You bewildering and bewitching winner of hearts, what was I led by before I knew you?’” That quotation is used as the caption for an illustration depicting a well-dressed man gazing at the photographer.

This outpouring of early twentieth century purple prose wouldn’t be of interest apart from one thing: my copy of Cupid in Hell has the inscription “Thurber’s father” with an arrow pointing to that photograph. I was able to confirm the identification by looking at known photographs of Charles L. Thurber. The storyline of Cupid in Hell meanders from Columbus to the banks of the Rio Grande. An El Paso newspaper ran an article about the book that concluded with the comment, “The book promises to be a sensation, the promise being furnished by Mrs. Wagner, the author.”

There’s no question that Cupid in Hell was a sensation in the Thurber household, but the question remains: what in the world was Charlie Thurber doing in Clara Eleanor Wagner’s book?

The Columbus City Directory for 1910-11 lists Wagner and her husband Eugene living at the Norwich Hotel. The building, no longer a hotel, is still standing at the northeast corner of Fourth and State Streets. Eugene was a cashier at the Grove City Savings Bank. The 1910 census shows the Wagners as residents of Grove City, where they had a summer home. The 1920 census indicates that Eugene has become president of the bank.

From 1908 to 1910 Charlie Thurber was a clerk in the office of the state dairy and food commissioner and for the next two years held various short-term political jobs.

How did their paths cross? In Cupid in Hell, Wagner mentions a friend of the protagonist who was accused by her husband of “indiscretions.” The friend’s explanation was: “I went with a man to look at some real estate, and tried to get some friends of mine political positions, and those were my indiscretions.” In an age that valued respectability, indiscretions were serious stuff.

Perhaps Clara thought that Charlie was the person to talk to if you had a friend looking for a political position. That can only be a guess. I haven’t been able to discover anything about the circumstances of how Charlie came to be in her book. Nor is there is any record of the reactions from Charlie’s wife Mame or his father-in-law, so we can only make conjectures; but because Mame was never shy about sharing her opinions and grandfather Fisher was immensely proud of his social standing, I think it’s safe to assume that there was nothing tepid in their responses.

It remains intriguing that in The Thurber Album Thurber included an account of Charlie in a predicament. It was one with comic overtones, relating how his father managed to get himself trapped inside a rabbit pen “where he was imprisoned for three hours with six Belgian hares and thirteen guinea pigs. He had to squat through this ordeal, a posture he elected to endure after attempting to rise and bashing his derby against the chicken wire across the top of the pen.”

Perhaps this narrative adumbrates his father’s humiliating experience of being caught in the Cupid in Hell crisis, although that, too, can only be a guess. Anyone who knew what actually happened back in 1910 has long since taken up residence at Green Lawn Cemetery. And Clara Eleanor Wagner died in

1944. The cause of death was listed as dementia.

To end on a cheerier note, I am proud to say that my family had a notable effect on James Thurber during his collegiate years. My family had a brewery prior to Prohibition, and in the early years of the twentieth century fraternities at Ohio State were known as Hoster Clubs.

Harrison Kinney enlisted me as a proofreader of the typescript of his definitive—and massive—biography of Thurber. In its published form James Thurber: His Life and Times comes to 1,238 pages including notes and index.

I was pleased that Harrison included a mock interview— Thurber interviewing Thurber—that Thurber wrote for the Dispatch on his experience of returning to Columbus as the co-author of The Male Animal. It is filled with nonsensical whimsy. Thurber explains, for example, that they tore down Tubby Essington (a famous drum major at Ohio State) to make room for the Statehouse. That causes a porter at Union Station to ask, “What I want to know, is what they made room for when they tore you down?” (Sadly prescient considering the fate of Union Station.)

Thurber concludes, “The old gentleman didn’t answer. He started off in a dazed kind of way, still talking to himself, in the general direction of Hoster’s Brewery.”