by Matthew S. Schweitzer

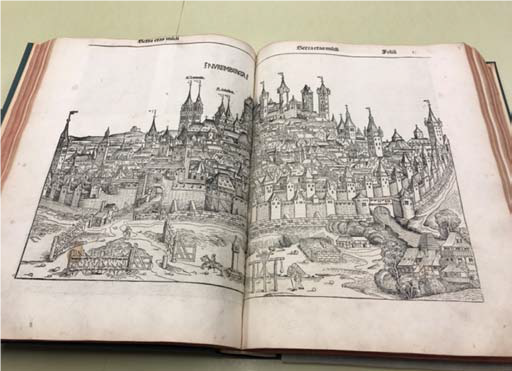

If the Gutenberg Bible is the most important and valuable printed book of the 15th century then the Liber Chronicarum, more commonly known as the Nuremberg Chronicle, is a close second. A marvel of early book production and illustration, the Nuremberg Chronicle is a massive work bursting with over 1,800 exquisite woodcut engravings produced by one of the preeminent printer-publishers of the 15th century, Anton Koberger. It is universally recognized as not only one of the most lavishly illustrated books ever made and a treasury of Renaissance art, but also an intriguing glimpse into a world on the cusp of great and momentous changes in science, religion, exploration, and the social structures of European civilization. Its publication marks the end of the Middle Ages and the beginning of the Early Modern Era. It represents a point in time at the dawn of the Age of Reason and for this and many other reasons, it is an artistic treasure of immense proportion.

Background

The Nuremberg Chronicle was published in 1493 in the city of Nuremberg, Germany, which had become a prominent printing hub in the decades after the introduction of the printing press by Gutenberg nearly forty years earlier. By the time of the book’s publication, Anton Koberger had already established himself as one of the great printers of that city having opened his first printing house there in 1470. Koberger became one of the most successful printers in Germany. At the height of his success, the business ran 24 printing presses and employed an army of 100 workers, which allowed him to produce a mountain of works on a wide variety of subjects over the course of his career. However, the Nuremberg Chronicle is by far his most famous and important production.

In December 1491, two Nuremberg merchants, Sebald Schreyer and Sebastian Kemmermeister approached Koberger about commissioning a grand publication: a profusely illustrated history of the world from Creation to Judgement Day. As part of the initial contract with Koberger, two Nuremberg artists, Michael Wolgemut and Wilhelm Pleydenwurif, were hired to create the numerous woodcut engravings. In fact, it was Wolgemut who had initially suggested the ambitious project to Koberger and helped to line up Sebald and Kemmermeister as the primary investors in what they were sure was to be a “best seller”. Hartmann Schedel, a local Nuremberg doctor and humanist, was engaged to write the text of the book. Schedel was well known for his extensive collection of printed books and manuscripts, which made a tremendous amount of knowledge available to him for references purposes. Schedel “borrowed” heavily from other earlier authors for his text, with particularly heavy influence from an earlier world history, the Supplementum Chronicarum, by Jacob Philip Foresti of Bergamo.

Two editions were planned by Koberger, a Latin and German translation. Georg Alt was hired to create the translation from the Latin text. This point alone is worthy of note since it made the book accessible to those who wanted to have a copy of the history of the world in their own native language and expanded the potential customer base beyond the typical university-educated scholar. The first copies of the Latin edition rolled off the presses in July 1493. The German edition appeared months later in December of the same year. It is estimated that 1500 Latin editions and 1000 German editions were printed. Customers could also pay extra to have their copies rubricated and have the woodcut engravings hand-colored to create an exceptionally luxurious book. A number of these hand-colored copies survive today and are held as iconic treasures by the collectors and institutions lucky enough to own them. Overall it is estimated that roughly 400 copies of the Latin edition along with about 300 copies of the German edition survive today.

Content

Overall the book is divided into seven periods or eras, each devoted to a separate segment of world history beginning with the Creation of the World as told in the Biblical Book of Genesis and ending with its destruction on Judgement Day according to the Book of Revelation. In between the story of Man on Earth is told in great detail, recounting mankind’s great achievements and disastrous failures. The book concludes with a massive world map showing the Earth as it was known at the close of the 15th century just prior to news of the discovery of the New World and the revolutionary changes it would bring.

The book’s frontispiece is a incredible full page woodcut engraving of God enthroned in Heaven, dressed in the garb of a Renaissance Pope. The throne is flanked by two columns which support an arch of branches upon which a group of Cherubim cavort wildly. Below, two hairy ape-like humanoid creatures hold large shields, initially left blank and intended to be filled in later presumably with the coat of arms of the book’s owner. The story of the creation and fall of Man are told with a series of large detailed illustrations. The stories of the Old Testament are conveyed as true history with the story of Moses and the Exodus, the foundation of Israel and the life of Christ told with large half and even full page engravings. Extensive genealogies are given connecting all the prominent historical figures back to Adam and Eve. Each of these figures is given a portrait to coincide with the passages relating to their place in the chronicle of history. Impressive cityscapes illustrate the various locales described in the text. By far the most impressive of these is a full two-page engraved view of the city of Nuremberg itself. Interestingly of the 1809 individual woodcuts included in the book, only 645 of them are unique. In many places the same engravings are used for different cities and portraits sometimes reused a dozen times across the book for various completely unrelated historical figures.

Artists

Without question the fame and notoriety of the Nuremberg Chronicle comes from its woodcut engravings. Michael Wolgemut and Wilhelm Pleydenwurif were the principal artists contracted to create the engravings for the book and while each was a prominent artist in their own right, they are probably best remembered for their contributions to the Nuremberg Chronicle. Wolgemut ran a well-known and respected artists workshop in Nuremberg and he himself is believed to have been the original impetus for the creation of the Chronicle from the start. Wilhem Pleydenwurif was Wolgemut’s stepson and assistant, Wolgemut having studied under Wilhelm’s father Hans and had married his wife after the master’s death in 1472. Wolgemut is also remembered as having apprenticed a young Albrecht Durer in his workshop for several years. Durer, who was godson to Anton Koberger, has long been thought to have possibly contributed some of the woodcuts for the Nuremberg Chronicle, although this is disputed by some who say that Durer was gone from Wolgemut’s workshop by the time work began on the book.

Without question the fame and notoriety of the Nuremberg Chronicle comes from its woodcut engravings. Michael Wolgemut and Wilhelm Pleydenwurif were the principal artists contracted to create the engravings for the book and while each was a prominent artist in their own right, they are probably best remembered for their contributions to the Nuremberg Chronicle. Wolgemut ran a well-known and respected artists workshop in Nuremberg and he himself is believed to have been the original impetus for the creation of the Chronicle from the start. Wilhem Pleydenwurif was Wolgemut’s stepson and assistant, Wolgemut having studied under Wilhelm’s father Hans and had married his wife after the master’s death in 1472. Wolgemut is also remembered as having apprenticed a young Albrecht Durer in his workshop for several years. Durer, who was godson to Anton Koberger, has long been thought to have possibly contributed some of the woodcuts for the Nuremberg Chronicle, although this is disputed by some who say that Durer was gone from Wolgemut’s workshop by the time work began on the book.

Perhaps what is even more unusual and of particular importance for art historians is the fact that much of the original artwork, layouts, and wood blocks used for the production of the Nuremberg Chronicle were preserved and exist today. We know that Wolgemut’s workshop had been working on designs for the book for years before its publication, perhaps as early as 1488 (which is why some scholars speculate that a young Durer could have worked on some of the preliminary artwork.). As part of the work contract, Wolgemut was required to submit manuscript layouts (called exemplars) of both the Latin and German editions to Schreyer and Kemmermeister . These exemplars were used to design the layout of the book and the interposition of text and illustration, which were used as a guide when executing the job of actually printing the book. The book’s patrons later had the copy of the Chronicle’s exemplars bound with their coat of arms displayed on the endpapers and preserved for posterity. Today Wolgemut’s pencil sketch design for the elaborate frontispiece is displayed in the collection of the British Museum.

Legacy

The publication of the Nuremberg Chronicle was largely a commercial success for its creators. In 1509 a financial accounting of the sales of the book showed that 600 copies of the book remained unsold, with blame for these unsold copies placed on the appearance of pirate editions of the Chronicle appearing not long after its initial publication. In fact we know that between 1496 and 1500 Augsburg printer Johann Schönsperger produced three “unauthorized” editions of the Chronicle in both Latin and German. These became known as the Augsburg Chronicle and contained a condensed version of Schedel’s text and all new artwork which copied the original closely. Schönsperger’s editions were in a much smaller 4to format and thus were considerably cheaper and appealed to the less affluent but literate customer.

As mentioned nearly 700 copies of the Nuremberg Chronicle survive today both in institutions and in private collections. The survival of so many varied copies along with the existence of the exemplars, original artwork, and legal contracts provide an incredible and unusually full picture of the history and production of this book. It is a treasure beyond compare for scholars, historians, artists, and book lovers.

A Parting Note

Here in Ohio we are lucky to have at least two copies of the Nuremberg Chronicle accessible to those interested in seeing this magnificent book in person. Ohio State University and the Toledo Museum of Art both have nearly perfect copies in their collections. Both copies have been rebound, but their contents are impeccably preserved. While neither of these copies are hand-colored or rubricated, the woodcut engravings are decidedly impressive up close. They represent a tangible link to the earliest era of the printed book and anyone privileged to see them in person will undoubtedly look upon them in awe for they are an extraordinary example of the Northern Renaissance made incarnate.

Editor’s Note: Kent State University holds two copies of the chronicle, one in each language and hand-colored. Both are available for viewing and research in Special Collections. If you want to read more about the conception, construction, and printing of the Nuremberg Chronicle, check out Adrian Wilson’s The Making of the Nuremberg Chronicle with an introduction by Peter Zahn (Netherlands: Nico Israel, 1976). You can also purchase books of the city plates from Dover Publications.

Correction: The two Kent State copies of the Nuremberg Chronicle are not, in fact, colored. They do however have a single hand-colored leaf from the book.

Today, a special nopalry (an organically certified cacti farm) exists in the state of Oaxaca as a way to bring back the important history of cochinilla in Oaxaca. It also provides many local crafts people with an organic natural source for red dye and other colors that can be obtained with additives. It was a pleasant surprise when a visit to the del Río Dueñas nopalry was added to our tour group itinerary at the last minute! I even had my book with me to read during the trip, as I was only half finished with A Perfect Red. A small museum was the beginning of our tour, followed by the nopal paddle greenhouse, and then the studio where artist interns are encouraged to experiment with the dye in their artworks. Our guide was artist and architect, Edgar Jahir Trujillo, and he sold his cochinilla painting of a winged insect to a member of our group. The painting technique he used involved dried nopal paddles, dipped in the red dye, to impress texture onto the wings of a male cochinilla insect.

Today, a special nopalry (an organically certified cacti farm) exists in the state of Oaxaca as a way to bring back the important history of cochinilla in Oaxaca. It also provides many local crafts people with an organic natural source for red dye and other colors that can be obtained with additives. It was a pleasant surprise when a visit to the del Río Dueñas nopalry was added to our tour group itinerary at the last minute! I even had my book with me to read during the trip, as I was only half finished with A Perfect Red. A small museum was the beginning of our tour, followed by the nopal paddle greenhouse, and then the studio where artist interns are encouraged to experiment with the dye in their artworks. Our guide was artist and architect, Edgar Jahir Trujillo, and he sold his cochinilla painting of a winged insect to a member of our group. The painting technique he used involved dried nopal paddles, dipped in the red dye, to impress texture onto the wings of a male cochinilla insect. After 15 days of incubation in the palm mat tubes, the females are removed and added to other insects brushed from the nopal paddles that were not used for breeding. Together, they are set out to dehydrate and die in the sun, or they could also be dried in an oven. The nopal paddle (only used once) is fed to animals or composted. One hundred forty thousand of the dried insects equals one kilo of cochinilla. If you squish a cochinilla insect in your palm, its blood reacts with elements in the skin, which affects the color. Thirty percent of the cochinilla powder is pure coloring agent (pure pigment) that will last forever, and will not react to the pH of different surfaces. The carminic acid in the insect protects it from viruses, but is also the most important element used for dye. To get the carminic acid from the powder made from the dried insects, water plus alum are added to make a liquid, the liquid is boiled, then it is put through filters. Two chemical additives that achieve color variations are: Citric acid from limes for less scarlet, more pink, and bicarbonate of soda for mauve (dark purple). Artist interns working at the nopalry can achieve many texture and color variations in their art through experimentation with additives.

After 15 days of incubation in the palm mat tubes, the females are removed and added to other insects brushed from the nopal paddles that were not used for breeding. Together, they are set out to dehydrate and die in the sun, or they could also be dried in an oven. The nopal paddle (only used once) is fed to animals or composted. One hundred forty thousand of the dried insects equals one kilo of cochinilla. If you squish a cochinilla insect in your palm, its blood reacts with elements in the skin, which affects the color. Thirty percent of the cochinilla powder is pure coloring agent (pure pigment) that will last forever, and will not react to the pH of different surfaces. The carminic acid in the insect protects it from viruses, but is also the most important element used for dye. To get the carminic acid from the powder made from the dried insects, water plus alum are added to make a liquid, the liquid is boiled, then it is put through filters. Two chemical additives that achieve color variations are: Citric acid from limes for less scarlet, more pink, and bicarbonate of soda for mauve (dark purple). Artist interns working at the nopalry can achieve many texture and color variations in their art through experimentation with additives. These fibers are first boiled with bicarbonate of soda. Mechanized Hollander beaters are used to further break down the fibrous pulp. Lots of water is used for soaking the fibers and water also helps with the swishing of the pulp when it is screened. (After use, the water is filtered and strained and treated so it’s fit to consume, then gets delivered to Oaxaca City by tank transport.) The paper screening technique involves swishing liquid pulp from side to side and then up and down in order to cross stitch the fibers, thereby evening out and strengthening the paper. This workshop has their own watermark embedded in the boxed screen, which leaves its mark in either bas or high relief; its design is a heart with a swimmer approaching. After swishing in the screen, the water is pressed out with big sheets of felt. They use synthetic/industrial felt as it’s easier to peel off, doesn’t decompose as fast, and so it gets reused. Then the pressed pulp sheet is turned out onto a zinc tin sheet to dry. The tin sheets are cut from recycled materials like construction siding. Before the paper dries they can press decorative indentations into it, or add decorative leaves or shiny mica bits. In the same workroom, hanging to dry, were molded paper portraits of historical Zapotec leaders we’d seen at one of the archeological sites with our tour group.

These fibers are first boiled with bicarbonate of soda. Mechanized Hollander beaters are used to further break down the fibrous pulp. Lots of water is used for soaking the fibers and water also helps with the swishing of the pulp when it is screened. (After use, the water is filtered and strained and treated so it’s fit to consume, then gets delivered to Oaxaca City by tank transport.) The paper screening technique involves swishing liquid pulp from side to side and then up and down in order to cross stitch the fibers, thereby evening out and strengthening the paper. This workshop has their own watermark embedded in the boxed screen, which leaves its mark in either bas or high relief; its design is a heart with a swimmer approaching. After swishing in the screen, the water is pressed out with big sheets of felt. They use synthetic/industrial felt as it’s easier to peel off, doesn’t decompose as fast, and so it gets reused. Then the pressed pulp sheet is turned out onto a zinc tin sheet to dry. The tin sheets are cut from recycled materials like construction siding. Before the paper dries they can press decorative indentations into it, or add decorative leaves or shiny mica bits. In the same workroom, hanging to dry, were molded paper portraits of historical Zapotec leaders we’d seen at one of the archeological sites with our tour group.

Once there, we were greeted very pleasantly in Jack and Barbara’s large, airy living room by Barbiel and her husband, John Saunders, as well as her brother John and his wife Cathy. “There’s coffee and light food in the kitchen!” we were told by our gracious hosts, who clearly were caught up in the opportunity to share bibliophily with us.

Once there, we were greeted very pleasantly in Jack and Barbara’s large, airy living room by Barbiel and her husband, John Saunders, as well as her brother John and his wife Cathy. “There’s coffee and light food in the kitchen!” we were told by our gracious hosts, who clearly were caught up in the opportunity to share bibliophily with us.